There is no extra stanza or concluding couplet to honor the fleeting joys of knowledge or to hope in human progress. Unlike many of his poems, “Ozymandias” does not end on a note of hope. Perhaps Shelley chose the medium of poetry in order to create something more powerful and lasting than what politics could achieve, all the while understanding that words too will eventually pass away. The only things that “survive” are the artist’s records of the king’s passion, carved into the stone.

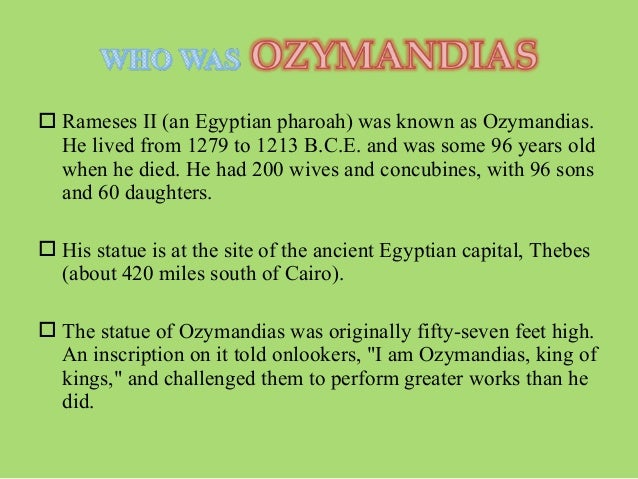

In a way, the artist has become more powerful than the king. Furthermore, the sculptor himself gets attention and praise that used to be deserved by the king, for all that Ozymandias achieved has now “decayed” into almost nothing, while the sculpture has lasted long enough to make it into poetry. It is not just the “mighty” who desire to withstand time it is common for people to seek immortality and to resist death and decay. More seriously, there are problems of transcription, for apparently Shelley’s poem does not even accurately reproduce the words of the inscription.įinally, we cannot miss the general comment on human vanity in the poem. For one thing, there are problems of translation, for the king did not write in English. Yet, communicating words presents a different set of problems. Poetry might last in a way that other human creations cannot. Our best access to the king himself is not the statue, not anything physical, but the king’s own words. The statue itself is an expression of the sculptor, who might or might not have truly captured the passions of the king. This helps create a sense of the mystery of history and legend: we are getting the story from a poet who heard it from a traveler who might or might not have actually seen the statue. It is important to keep in mind the point of view of “Ozymandias.” The perspective on the statue is coming from an unknown traveler who is telling the speaker about the scene. Note the use of alliteration to emphasize the point: “boundless and bare” “lone and level.” Everything about the king’s “exploits” is now gone, and all that remains of the dominating civilization are shattered “stones” alone in the desert. The lesson is important in Europe: France’s hegemony has ended, and England’s will end sooner or later. By Shelley’s time, nothing remains but a shattered bust, eroded “visage,” and “trunkless legs” surrounded with “nothing” but “level sands” that “stretch far away.” Shelley thus points out human mortality and the fate of artificial things. The statue and surrounding desert constitute a metaphor for invented power in the face of natural power. That principle may well remain valid, but it is undercut by the plain fact that even an empire is a human creation that will one day pass away. The original inscription read “I am Ozymandias, King of Kings if anyone wishes to know what I am and where I lie, let him surpass me in some of my exploits.” The idea was that he was too powerful for even the common king to relate to him even a mighty king should despair at matching his power. The final five lines mock the inscription hammered into the pedestal of the statue. The “heart” is first of all the king’s, which “fed” the sculptor’s passions, and in turn the sculptor’s, sympathetically recapturing the king’s passions in the stone. Egyptian King Ramses II, whom the Greeks called “Ozymandias.” The traveler describes the great work of the sculptor, who was able to capture the king’s “passions” and give meaningful expression to the stone, an otherwise “lifeless thing.” The “mocking hand” in line 8 is that of the sculptor, who had the artistic ability to “mock” (that is, both imitate and deride) the passions of the king.

The title of the poem informs the reader that the subject is the 13th-century B.C. Here we have a speaker learning from a traveler about a giant, ruined statue that lay broken and eroded in the desert. Although it is neither a Petrarchan sonnet nor a Shakespearean sonnet, the rhyming scheme and style resemble a Petrarchan sonnet more, particularly with its 8-6 structure rather than 4-4-4-2. "Ozymandias" is a fourteen-line, iambic pentameter sonnet. There also was a pedestal at the statue, where the traveler read that the statue was of “Ozymandias, King of Kings.” Although the pedestal told “mighty” onlookers that they should look out at the King’s works and thus despair at his greatness, the whole area was just covered with flat sand. The sculptor interpreted his subject well.

The face was sunk in the sand, frowning and sneering. The first-person poetic persona states that he met a traveler who had been to “an antique land.” The traveler told him that he had seen a vast but ruined statue, where only the legs remained standing.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)